Work Starts

First of all the mess had to be cleared up. Cunard's crew had been flown straight home upon arrival, and the breakfast of the 9th was still on the tables. All unused food had to be disposed of quickly, as there was no power now to run the refrigerators.

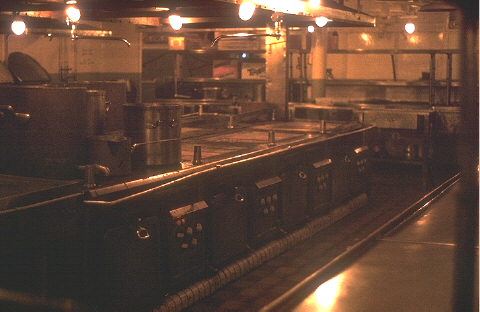

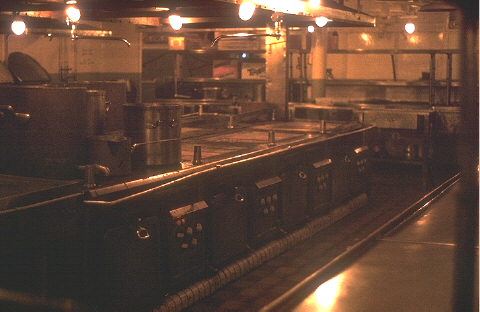

The kitchen area after cleaning, and before it was ripped out.

The first problem that arose was a dispute between land-based and maritime unions as to who had the right to do the conversion work on the ship. It was at last determined by the US coast-guard that since the propellers were immobilized and the ship was so tied to the land that tools would be needed to set her adrift, and if the owners have no intention to sail her, then for legal purposes, she was (and is) a building.

Drydocking

On April 6th, 1968, the ship was towed into the US naval drydock in Long Beach where approximately 90 hull openings were sealed, 3 of the 4 propellers were removed. This included the removal of the stabilizer fins mentioned previously, and a 125 ton steel "viewing" box was constructed around the port-outer propeller. The entire hull was stripped of paint and painted again with 6,500 gallons of fresh paint claimed to last 25 years. This work cost $679,550.

The Queen Mary is dragged into the Long Beach Naval Shipyard's drydock at the beginning of her conversion work.

The ship just after the water had been pumped out. The propellers are covered with marine growth

A special paint is applied to the hull. It has kept the ship in good condition even until today.

A metal box is welded onto the hull around the port-outer propeller. Today, visitors can enter this box to see the propeller in the water.