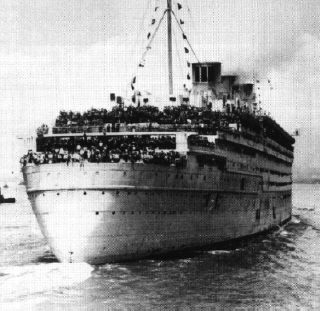

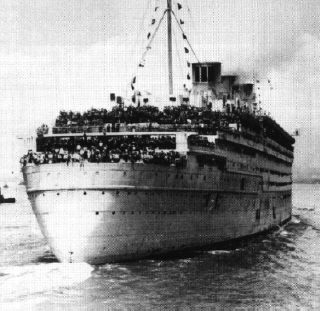

The Queen

Mary is crammed with men. She still holds the record for the largest number of people on

one vessel at one time.

The Queen

Mary is crammed with men. She still holds the record for the largest number of people on

one vessel at one time.

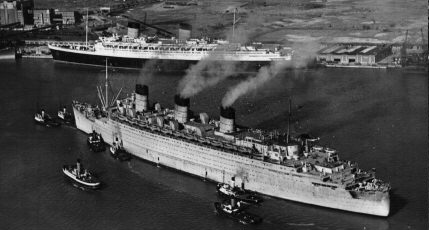

The Queen Mary was often called the Gray Ghost during the war because of her color and the way she traveled secretly about the globe.

The Queen Mary left Southampton on August 28 1939 packed with people trying to flee to America in the face of the threat of war in Europe. This was to be the ship's last peacetime voyage, for she arrived in New York to find that war had been declared between Britain and Germany on 3 September. Even before this, the portholes had been painted over to offer less of a target to submarines.

The Queen Mary stayed at her berth in New York for six months, before orders were received to paint the ship in camoflage gray. She then sailed for Cape Town, South Africa, and from there to Sydney, Australia where her luxurious fittings were removed, and bunk beds were installed to enable her to carry troops. The Queen Mary then took 5,000 men to Gourock, Scotland. Later troop carrying voyages were to take her all over the world, to places such as Bombay, Suez, Florida, and frequently Sydney again and Singapore, where she was drydocked twice. Work was carried out here to service the engines, and the ship was even given guns on Sun Deck as a measure against both aircraft and surfaced submarines.

The Queen

Mary is crammed with men. She still holds the record for the largest number of people on

one vessel at one time.

The Queen

Mary is crammed with men. She still holds the record for the largest number of people on

one vessel at one time.

Eventually, the ship's troop-carrying capacity was increased to 16,000 men. She could move an entire army division in one voyage. This was an incredible feat, duplicated by the Mary's sister ship the Queen Elizabeth, which had also been adapted for troop-carrying. It was not comfortable. Soldiers on board took turns in the bunks, sleeping in shifts as there were not enough bunks for all the men.

The Queen Mary was intended for the North Atlantic weather, and it transpired that she did not have adequate ventilation for the tropical climates she sailed through. Many men died from heat-exhaustion. Nevertheless, Churchill (who was occasionally a passenger during the war under the pseudonym "Colonel Warden") later said that the two "Queens" had shortened the war by a year. It was not surprising that Germany tried to destroy the ships, and it was rumored that Hitler offered the Iron Cross and a huge sum of money (some said $250,000 USD) to any U-Boat captain who could sink either of the Queens.

The Queen Mary's greatest defense against torpedoes was her speed. Sailing at 28.5 knots, the Mary was a fast moving target, much faster even than a warship could manage, and very difficult to aim at. To make it even more difficult, she zig-zagged at regular intervals, following set patterns.

One

day, 2 October1942, an escorting warship, HMS Curacoa, which had been sent to meet and

protect the Queen Mary on her approach to Britain, misjudged the liner's speed and

zig-zag. The Queen Mary hit the Curacoa amidships, cutting it in two. 331 of 432 crew were

lost from the Curacoa. Crew on the much larger Queen Mary felt only a small bump. The

liner could not stop for fear of lurking submarines, and had to steam onwards (the crew

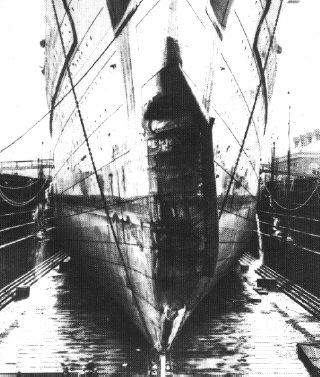

had orders to this effect) but at a reduced speed of only 10 knots. It was the worst incident in the Queen Mary's career. The

Queen Mary's bow was badly bent. The damage was patched up with cement, and later made

better in Boston, but the damage was not fully repaired until after the war when a new

stem was fitted.

One

day, 2 October1942, an escorting warship, HMS Curacoa, which had been sent to meet and

protect the Queen Mary on her approach to Britain, misjudged the liner's speed and

zig-zag. The Queen Mary hit the Curacoa amidships, cutting it in two. 331 of 432 crew were

lost from the Curacoa. Crew on the much larger Queen Mary felt only a small bump. The

liner could not stop for fear of lurking submarines, and had to steam onwards (the crew

had orders to this effect) but at a reduced speed of only 10 knots. It was the worst incident in the Queen Mary's career. The

Queen Mary's bow was badly bent. The damage was patched up with cement, and later made

better in Boston, but the damage was not fully repaired until after the war when a new

stem was fitted.

There are many theories today as to how the cruiser got so close to the speeding liner as to put herself in such danger. A court hearing heard evidence from both Curacoa and Cunard officers and found the Curacoa's officers at fault. A subsequent appeal apportioned one third of the blame to the Queen Mary. Though witnesses said they had seen officers on board the Curacoa taking photographs of the Queen Mary, it was not decided in court that this was a reason for the proximity of the two ships. It seems merely to have been a tragic misjudgement.

The Queen Mary's bow is bent after the impact.

After the war ended, the Queen Mary not only served to take American and Canadian G.I.s home, but also the wives they had met and married in Britain. The Queen Mary carried about 10,000 of these brides (about a third of the total), along with 3,700 children. At this time, the bunk beds had been removed from the ship, and later in September 1946 she began a ten month refit during which she was returned to her pre-war condition and color. Radar was also fitted to her at this time. She resumed her normal transatlantic service on 25th July, 1947.

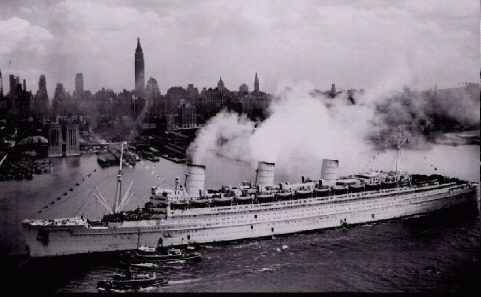

The ship arrives back in Southampton and is released from war service. Note that her funnels have already been painted in Cunard colors again, after being completely gray during the war.